Collage/Montage

Collage techniques are perhaps as old as the invention of paper in China over 2000 years ago. Collage's venerable history stretches from its early moments in the far east to its extensive practice in some form or another throughout medieval Europe and into the 19th century. Throughout history there was, according to Freya Gowrley: [A] wide range of composite visual, material, and textual forms of production that were pervasive, and which included the creation of traditional paper collage, assemblage, bibliographic objects such as scrapbooks and albums, scientific objects like herbaria, and craft practices such as paper cutting, quilting, and the creation of shellwork and Featherwork. Indeed, though the term collage is most often associated with paper, art history has long witnessed a diverse proliferation of assembled forms. 1. Before collage was given prominence as a fine art technique by Braque and Picasso in the early 20th century the practice was more than simply a domestic matter employed in the collecting of mementos, souvenirs, and other ephemera in scrapbooks and the like. However, this common lineage connects the practice of collage to the everyday world, which is one of its lasting strengths. By using the stuff of daily life, particularly the discarded material of print culture, the early collage worker, scrapbook maker or artist, was not just recycling or repurposing used material, but in a sense condensing it in an effort to distill some meaning from the material; to reshape it in personal ways that transcended its original purpose as a collective source of knowledge, information, or amusement. That process of condensing and reshaping print material appropriated from various sources continues, abetted by the artist's intelligence, sensibility, and individual style, breathing new life into its images and/or texts, transforming the quotidian in ways that are often poetic. This transformation begins with the recognition of some extra-ordinary potential either ascribed to or inherent in the material, a quality or qualities that might be amplified through careful reflection upon both the substance and content of the material as well as its form and structure. Traditional collage and montage techniques are closely related in formal and material ways. Given that both collage and montage are not medium specific techniques there is often some overlap between collage and montage. And yet, there is a provisional distinction between the formal properties of collage and those of montage in relation to how each articulates meaning. Scholar Magda Dragu argues that collage and montage involve different types of meaning formation: Heterogeneous for collage and homogeneous for montage, with the stipulation that montage might sometimes be heterogeneous, or exhibiting a narrative without a clear meaning. Dragu asserts: The opposition heterogeneous-homogenous relates not only to formal organization, but also to meaning formation, outlining unclear versus clear meaning, respectively. 2. Dragu’s theoretical distinction regarding the clarity of one or the other is conditional, as some collages are clear as to their meaning and some montages unclear. Indeed, she suggests as much, writing: However, one cannot talk of complete confusion and obfuscation of meaning in all visual collages or all heterogeneous photomontages … 3. The underlying condition or issue seems to involve the "pictorial logic" or lack thereof, of collages and montages. For example, a pictorially homogeneous montage (or photomontage) might make sense as a picture and yet be unclear as to its meaning. Works of "magical realism” in both painting and film seem good examples of this.

Freya Gowrley, Introduction, Fragmentary Forms, A New History of Collage, Princeton, 2024. 10

Magda Dragu, Introduction, Form and Meaning in Avant-Garde Collage and Montage, Routledge, 2023 xxi.

Introduction, xx.

Vegetal Man 2005 Collage over medical chart & enamel on board, 34 x 49 inches.

The plant kingdom and the animal kingdom seem worlds apart. But the division between these realms is in fact illusory, as nearly all higher order animals, including humans, host an abundance of microscopic flora and fauna. Fully understanding our relationship to the natural world involves the recognition of our interdependence with it. Vegetal Man is meant to symbolize that interdependence. This large collage is made of fragments of a wide variety of plant and fungi illustrations selected from botanical books and other sources. The illustrations making up the collage are layered over an enlarged illustration of a human skeleton and various plant and fungi shapes were selected to approximate the morphology of the bones. In addition to this the illustrations were also selected to suggest a rough chronology: Beginning at the feet are the most primitive flora; lichens, mushrooms, and ferns, ascending through herbs, wild berries, and woody plants to culminate in cultivated flowers, fruits and vegetables in the head of the figure.

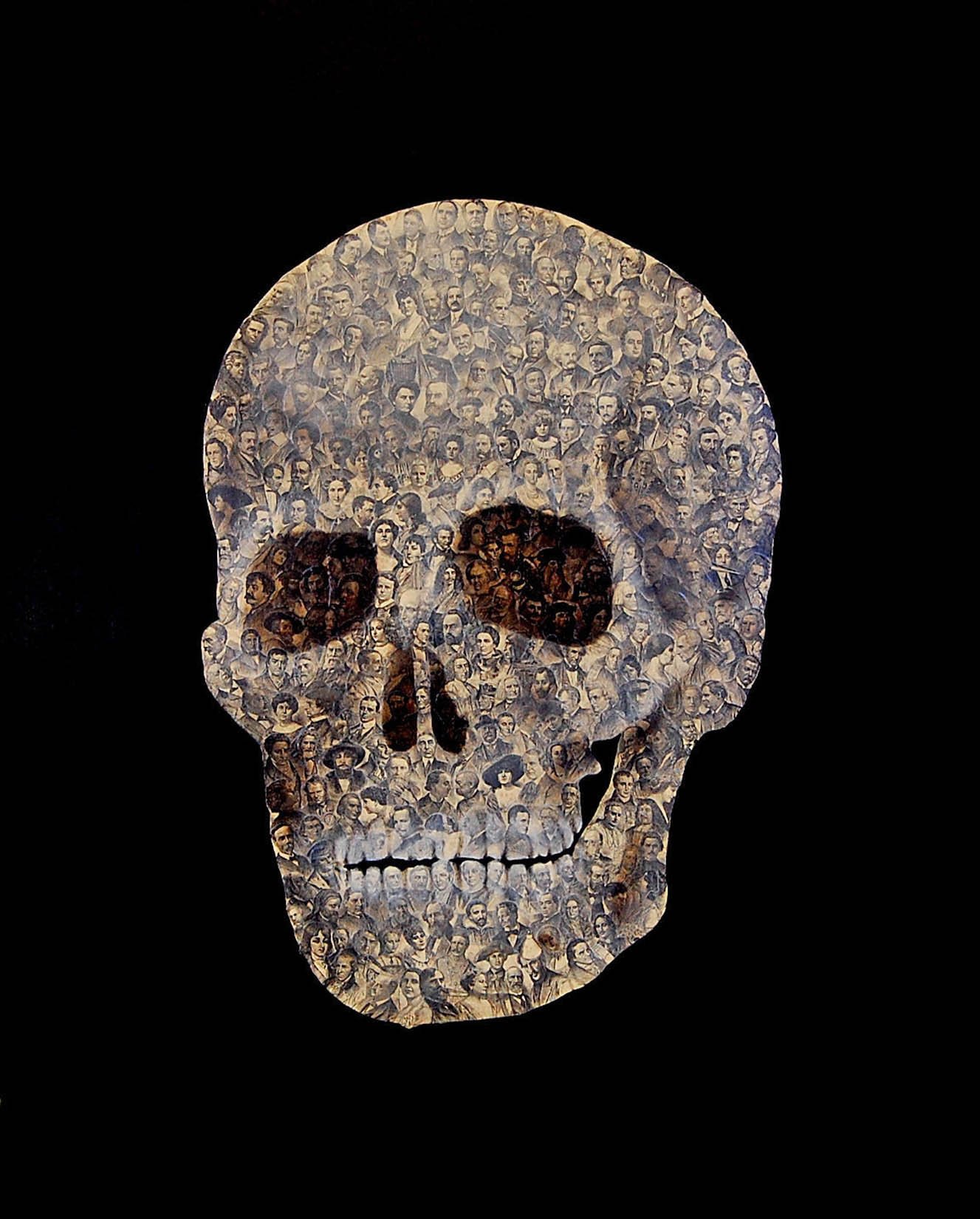

History Lesson (Memento Mori) 2009 Montage and mixed-media on board, 32x40 inches. Right: detail.

Garden Chair 2011 Collage and mixed media on board, 32x40 inches (Private collection).

Desert Parcel (Book fragments) 2013 Collage on canvas, 39.75x54.75 inches.

The material comprising Desert Parcel (Book fragments) – the dry and brittle crushed pages from an old book – is used to form a literal ground: A base or foundation of sepia-toned particles glued to a rectangular support. As ground in this sense, Desert Parcel can be appreciated in terms of its physical properties, such as its texture or material density, or simply by virtue of the work’s presence as a two-dimensional object: A large swath of fragmented paper that reduces the technique of collage to a bare minimum. But this reduction also involves transforming fragmented book pages into a kind of picture (a picture, as it were, of “archeological” fragments replete with traces of text and images). While this literal image is compelling in its own right, the work acquires cognitive depth when its physical properties are perceived in the context of the literary source of the material: Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt, published by D. Appleton & Company, New York, 1896. Based upon the use of these crushed pages as an artistic medium, the material can be seen to literally embody the concept of ground, and also effectively becomes a visual metaphor for a patch of desert.

Shattered Illusion 2014 Photo collage, hand-colored photocopies on board, with wood frame, 49x41.5x2.5 inches.

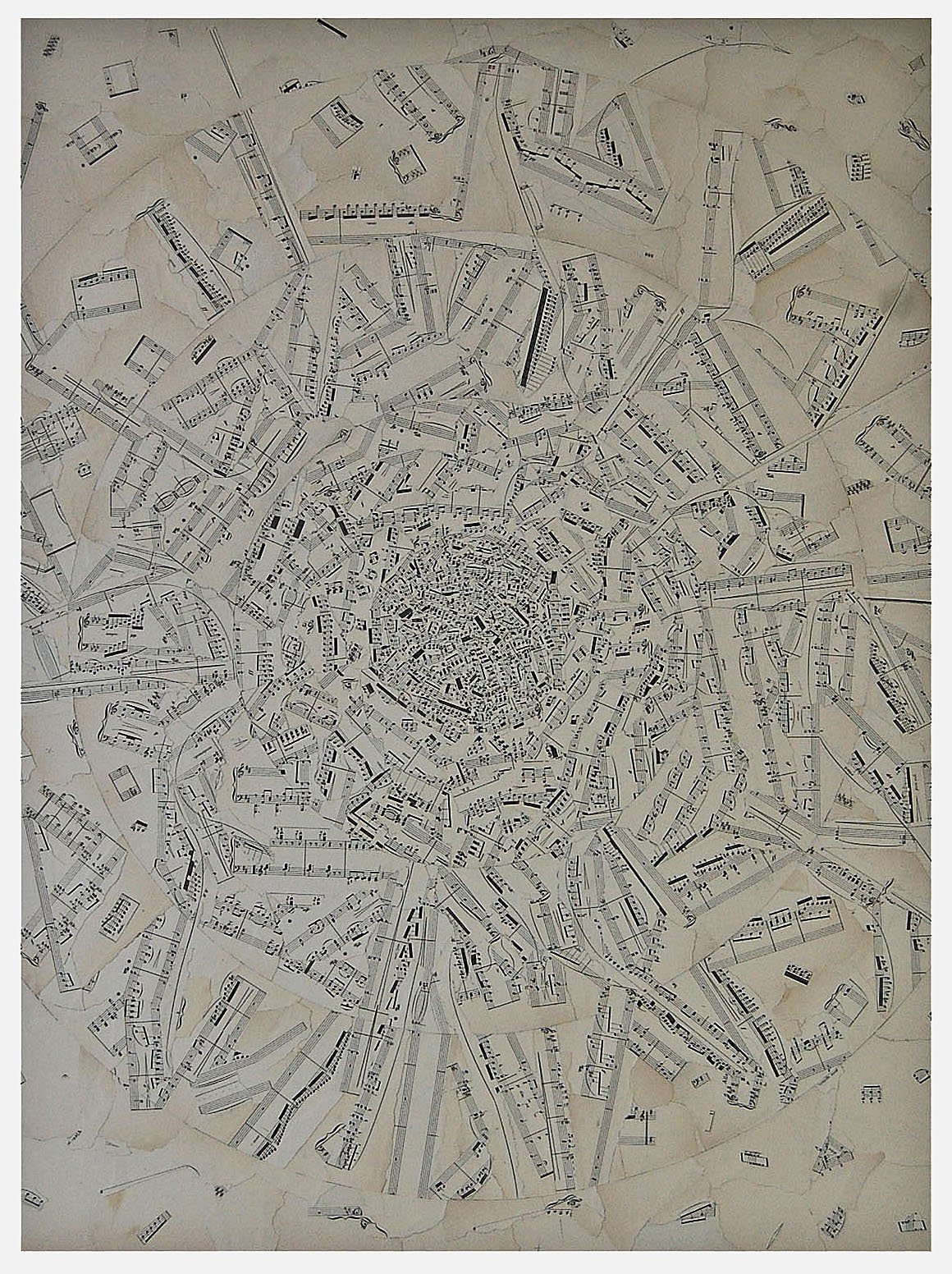

Pulse Collage 2014 (sheet music) on board, 32x40 inches.

Pulse is made from cut and torn fragments of sheet music arranged in a series of concentric circles, denser in the center and radiating out. This radiating structure or composition uses musical notes to represent sound waves. The notes are disrupted or scattered in a way that utilizes the varying density of the printed symbols as the visual equivalent of an explosion of sound. Music, basically sound in a medium (air), represented by musical notation, is systematically rearranged in the work and presented as an abstract, cacophonous burst or pulse. Musical notes are usually combined to form compositions: Sets or systems of symbols that represent pitch, duration, and so forth. The concept of “pitch” is particularly relevant to this work especially when defined in terms of vibration: the degree of highness or lowness of a sound. The varying density of the concentric rings of musical notes produces a visual or concrete sense of pitch and dissipation.

Veil 2014 Collage on board, 8x11 inches.

Veil pays homage to a pre-eminent dadaist work by Marcel Duchamp while also raising questions about the unintended or ironic significance of the inscription that Duchamp appended to this work, which is also its title. The work is Duchamp's infamous L.H.O.O.Q., of 1919: A small, color reproduction of the Mona Lisa to which Duchamp added a pencil thin mustache and those five letters. With Veil, only the background and the hands of the image remain in play, the figure largely replaced by a veil of text. The text, in white font on a black field, is part of an encyclopedia page on words beginning with the letter "X." The veil of words may suggest a figure in a Middle East burka, a reading perhaps enhanced by the background terrain, but as interesting as this might be, it has little to do with the intention of the work. The real point of Veil is located in the question mark at the end of those five mysterious letters.

Duchamp's original provocation, it must be noted, hinged on those letters, which, when uttered in French, deliver a phonetic pun: Elle a chaud au cul. Roughly translated this means: "She has a hot ass," or as Duchamp delicately put it: "There is fire down below." So what did Duchamp mean by this remark? The symbolic desecration of a reproduction of Leonardo Da Vinci's iconic masterpiece, including the vulgar expression written below the retouched image, was perhaps the perfect dadaist gesture; a radical challenge to the conservative aesthetics of Duchamp's day. As expected, such a challenge also created some controversy, and Duchamp relished controversy. So when it was suggested that his gesture was related to Sigmund Freud's speculations about Leonardo's sexual proclivities, Duchamp naturally agreed. But this tells us nothing essential about L.H.O.O.Q. I believe that the figure of Leonardo's Gioconda represents for Duchamp "the Bride," that is, art itself, something that in Duchamp's mind required a makeover, amounting to a "masculinizing" of art. Henceforth art would become primarily a matter of the mind, the “retinal” be damned. The textual content of Veil suggests as much given its focus on the lives of certain philosophers, but qua text it is simply meant to signify language, theory, intellect or mind. The question of just what is beneath this "veil" covering the body of our bride is the crux of the matter. The "X" of the portrait can be variously interpreted as standing for a location (as in "x" marks the spot), or as a sign for both the "unknown" and "negation." The spot, of course, marks the head, representing perhaps the unknown identity of the figure, or more importantly, the ultimately unknown nature of mind itself. "X" can also signify negation, in this case, the absence of feeling, the sensual, or even the "aesthetic." So, if we are to believe Duchamp when he remarked that those five cryptic letters meant "There is fire down below," then Veil seems ironic in so far as it questions the nature of the passion (if it can be called that) of art that is intended to only engage its audience intellectually. Beneath the veneer of language that constitutes her veil our bride is still made of flesh and blood. For more on Marcel Duchamp go to this link.

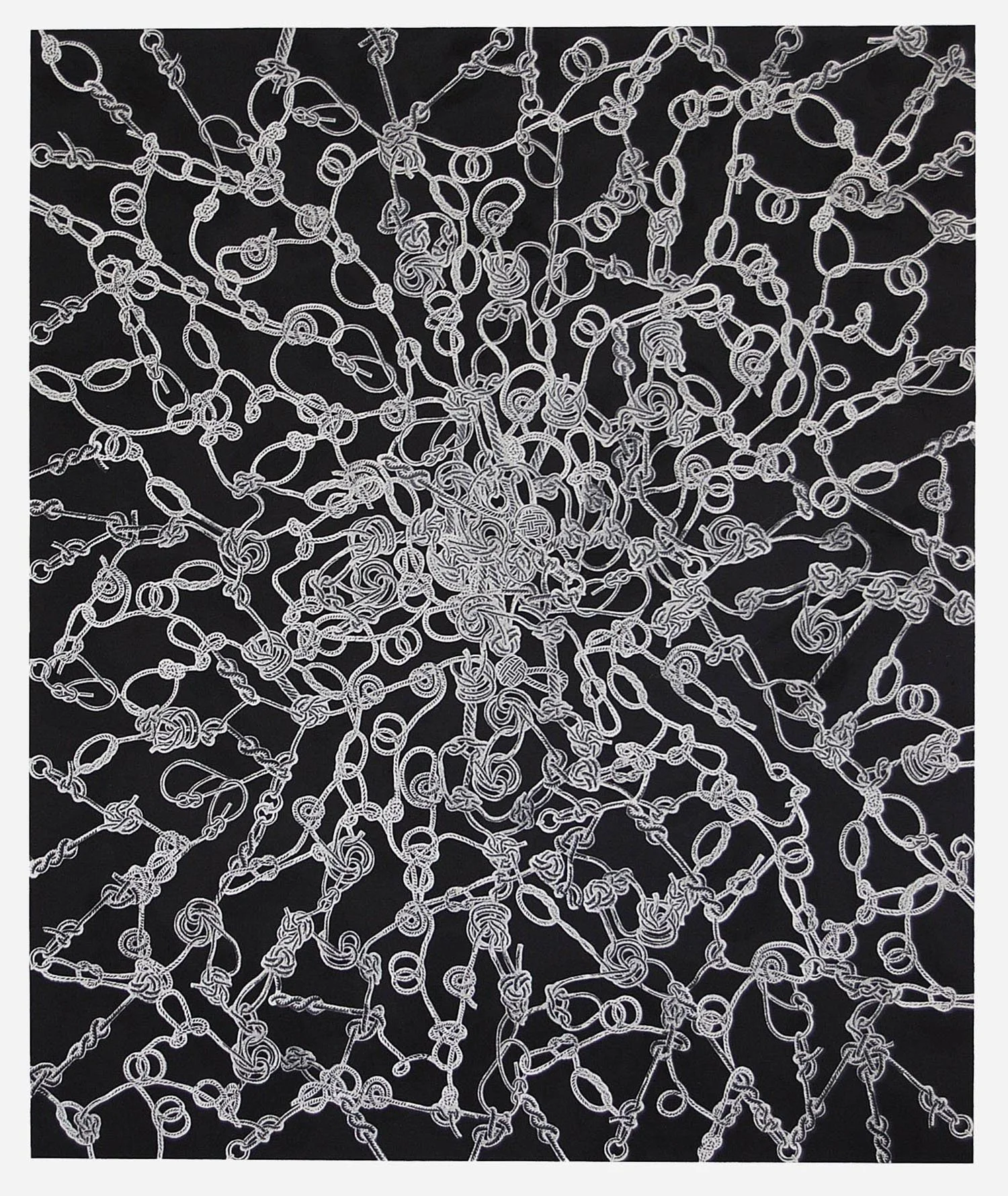

Tangle 2015 Photo collage, photocopies and enamel on board, 36x36 inches.

Tangle is a photo collage woven from scores of small knot diagrams tied together on a black field. The diagrams were taken from a dictionary entry on “Knots.” The little knot illustrations were first copied from the dictionary page, cut into individual pieces and printed enlarged and in negative to become the material for a large, virtual net or skein of tied together knots. Assembling this tangle of diagrams required using some of them unaltered, and cutting others into workable parts or segments; trimming or modifying as needed and then connecting the illustrations in ways that seemed congruent with the ways that actual knots might be tied together.

A couple of things are apparent upon closer inspection of this work: the skein of knots is denser in the center and the entire ensemble appears anchored at the outer edges of the work’s frame, which is delineated by a narrow band of canvas. This connection to the edges of the work (essentially its material support) creates a subtle illusion of suspension: a snarled trompe l’oeil net held in a frame. The work is formally abstract, and yet given the specific nature of the illustrations, the illusion of their suspension brings with it another sense of abstraction, one that is specific to the medium or technique of collage. The collage technique of cutting and tying pieces of knot diagrams in a myriad of ways becomes reflexive, sui generis, given the subject matter of the work.

Equation (2015) Photo collage, photo copies and enamel on board, 59.75 x 37.75 inches.

Equation is a work that seems impenetrable, in much the same way that a newly discovered language is, or an indecipherable code. While recognizable as a collage, the work at first doesn't seem to offer much aesthetically; rigorous to a fault it appears as little more than a formal exercise in the placement of repetitive shapes or illustrations, literally and figuratively a puzzling operation with no apparent rhyme or reason. Equation is a perfect example of a Postmodern artwork that philosopher Paul Crowther posits: “Uses form as a vehicle for ‘content’ and for a semantics of symbolism and association.” (Crowther, 2019) The first impression of Equation is that of a pattern of illustrations or shapes on a black field. That pattern is indistinguishable from the pictorial nature of the elements that constitute it, a series of illustrations of lab vessels arrayed in rows as if on invisible shelves. Like some alien "script" these elements, photocopied illustrations appropriated from an old chemistry textbook, were printed slightly enlarged and in negative (white lines on black), cut into parts or sections and carefully composed to form five interconnected lines of retorts, vials, tubes, and so forth. The illustrations and/or their constituent parts were then glued together in five tiers or rows on a black field, the reconstructed or composed material perhaps vaguely suggesting a cipher, or a series of glyphs. The black background serves to highlight the illustrations much like pictures or notations on a blackboard. The visual rhythm of the connected images of glassware lends the work a visually poetic quality, the shapes dancing from left to right and back again. The subject matter of Equation, rows of lab equipment, also contributes something to the poetry of the work by way of a visual pun, implying that the work itself is an experiment, or experimental. Equation is a kind of "picture language." Although the vessel illustrations have no lexical function or structure, the string of images are analogous to lines of symbols and invite the viewer to "read" them much as one would an equation. The movement of the eyes across the surface of the work can make the perceptive viewer-reader aware of the underlying cognitive relation between seeing and reading. The semantic force of Equation lies entirely in its formal structure and the symbolic meaning of the pictured vessels as experimental apparatuses. In brief, the experiment involves changing or transforming the practical use of the illustrations from that of picturing containers of chemical processes to a form of visual poetry that presents or re-presents this process as a metaphor for aesthetic and/or cognitive change.

Paul Crowther, Geneses of Postmodern Art, Technology as Iconology, Routledge, 2019, p. 11

Dark Web (Machinations) 2018 Photo collage on board, 40x60 inches.

Dark Web (Machinations) seems at first non-representational, or formally “abstract,” although its elements or components are recognizable as delineations of gears or machine parts. A large collage made from about a dozen photocopied diagrams of gear mechanisms, enlarged and printed in negative (white lines on a black field), the work represents a troubling aspect of contemporary life by way of a visual metaphor. The title of the work alerts the viewer-reader to this representational aspect and is in keeping with the visually intricate, almost diaphanous web of lines that make for a bewildering, overlapping network. “Dark Web” is, of course, the term for that part of the internet where immoral, illicit, and even criminal activity festers. In a sense, it is the sinister, dark underside of the brave new (digital) world. If the internet can be somehow compared to the human psyche, the machinations of this dark realm are not unlike, or in some ways parallel to or are correlated with, the unconscious. The Dark Web is infamous as an underworld of intrigue, pitfalls, shadows and dark corners: The purview of hackers, spies, pornographers, and terrorists, which are in some ways analogous to the manifestations of the unconscious. But unlike the unconscious, whether personal or collective, it is questionable if there is anything redeemable or potentially creative in what the Dark Web churns up. On the other hand, it might be argued that this is a raw, darkly creative realm in spite of or because of its moral, ethical, and legal entanglements. Whatever, the underside of the internet, much like the unconscious, sometimes erupts into the digital daylight, bringing unwanted and often disturbing intrusions. In fact, for many the mesmerizing allure of the internet, its growing control over many lives, and its expanding influence in social, political and economic matters and its subtle and not so subtle erosion of our sense of reality, may be changing the nature of human consciousness, a development that may be contributing to our growing isolation if not alienation from each other and the physical or natural world. The Dark Web to some extent represents a kind of technological or digital psychosis.

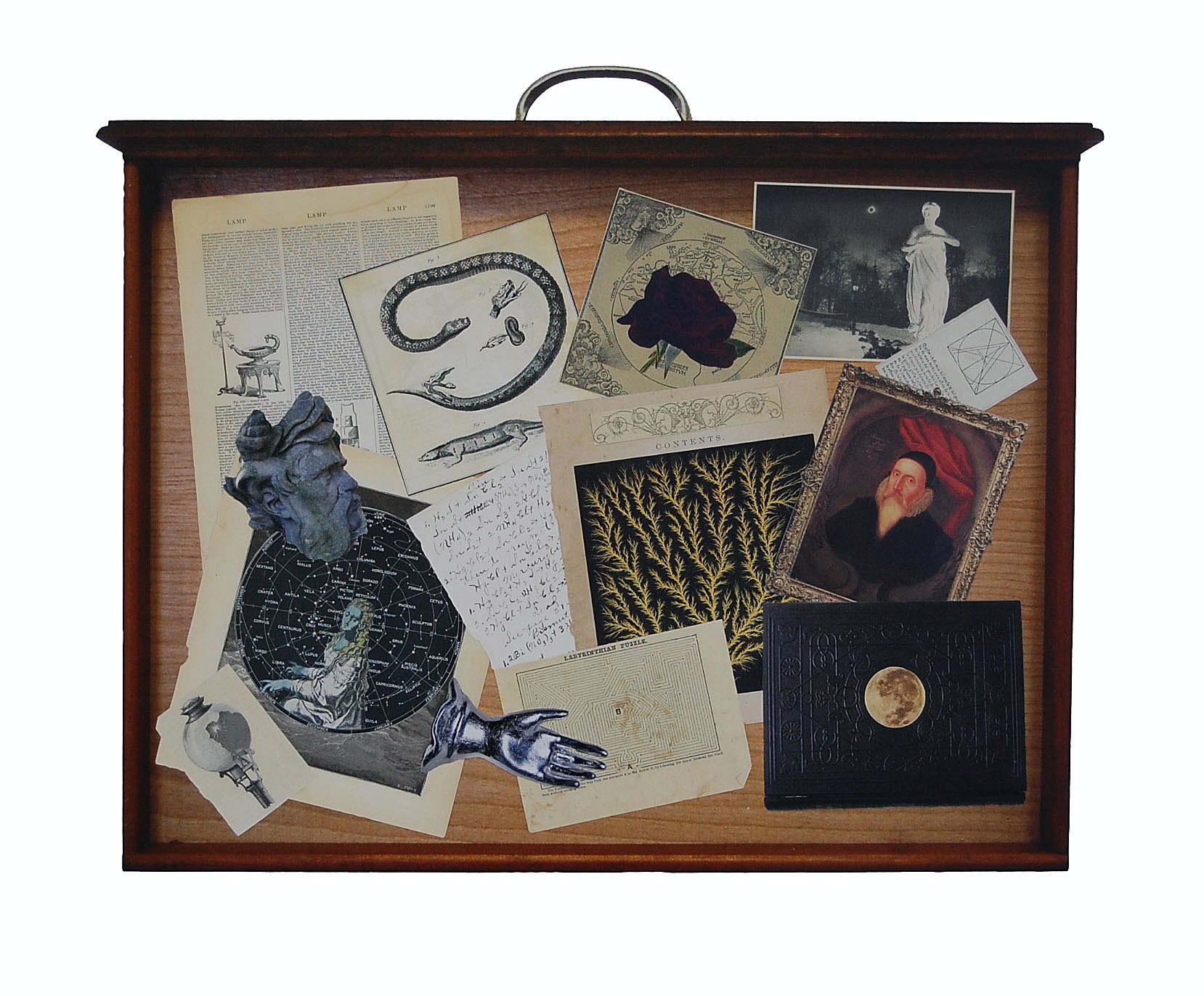

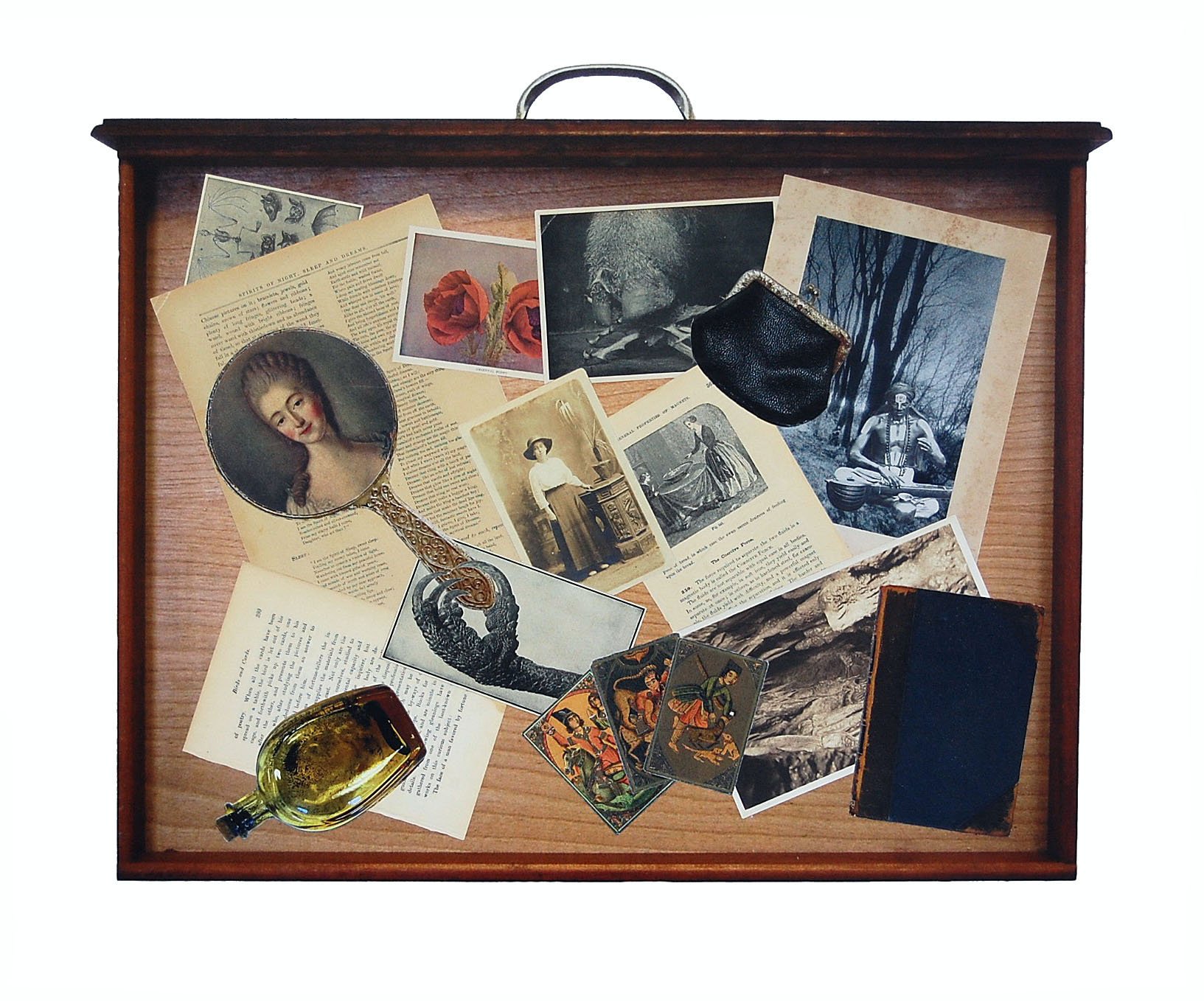

Recollections 2018 Photo collages, cut and fitted photocopies on drawer photos, four of an edition of 10, each 25.5 x 30.75. inches.

Swollen Seed 2020 Montage, illustrations on book page, 10x11.25 inches.

Shadows and Names 2020 Montage, ink and photocopies on illustrated book page, 10x12.5 inches.

Top left: Chasm 2024 Montage on board, 14x31.25 inches. Top right: Bird’s Eye View 2024 Montage on board, 13x30 inches. Bottom: Midnight Hour 2024 Montage on board, 12.75x26.75 inches.

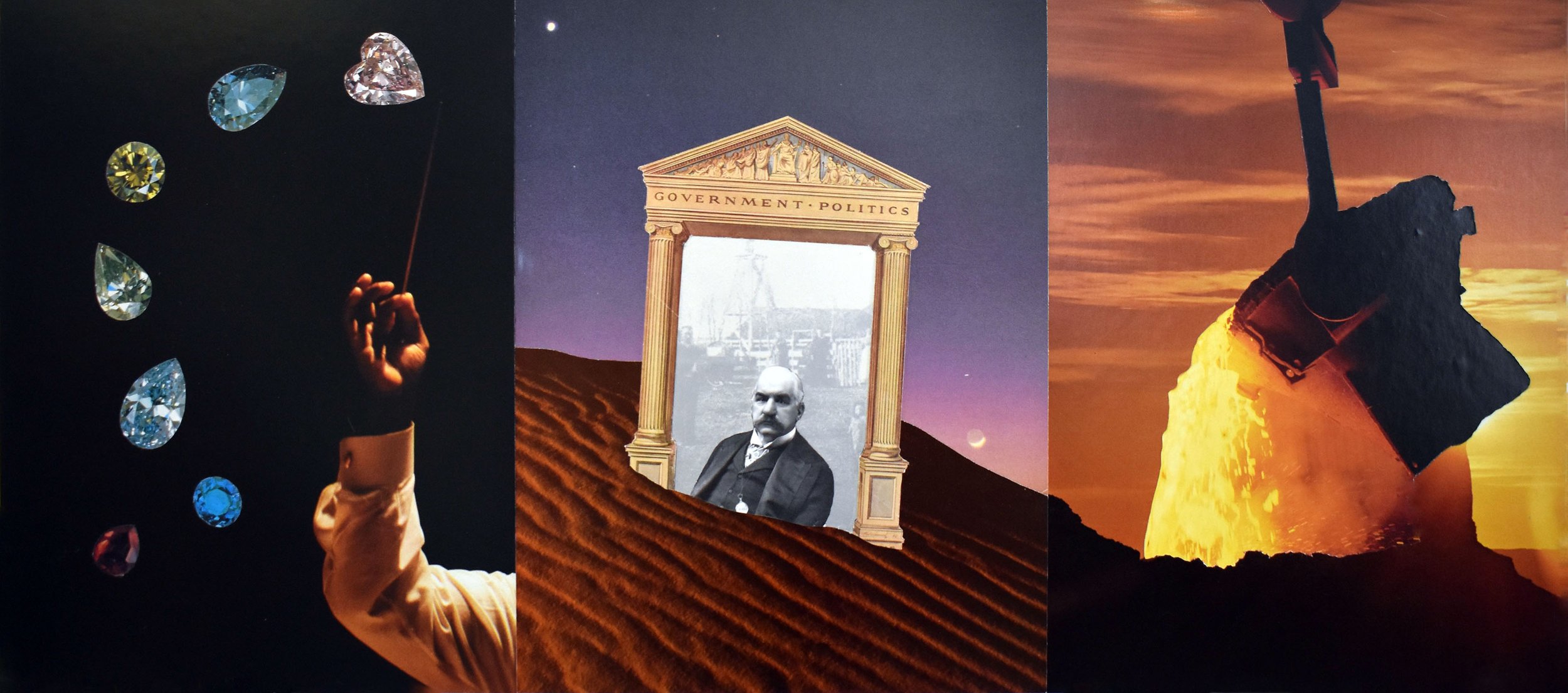

Top: Orchestration 2024, photomontage on board, 14.75 x 30.75 inches.

Bottom: Pirate’s Tale 2024, photomontage on board, 13.25 x 28.5 inches.

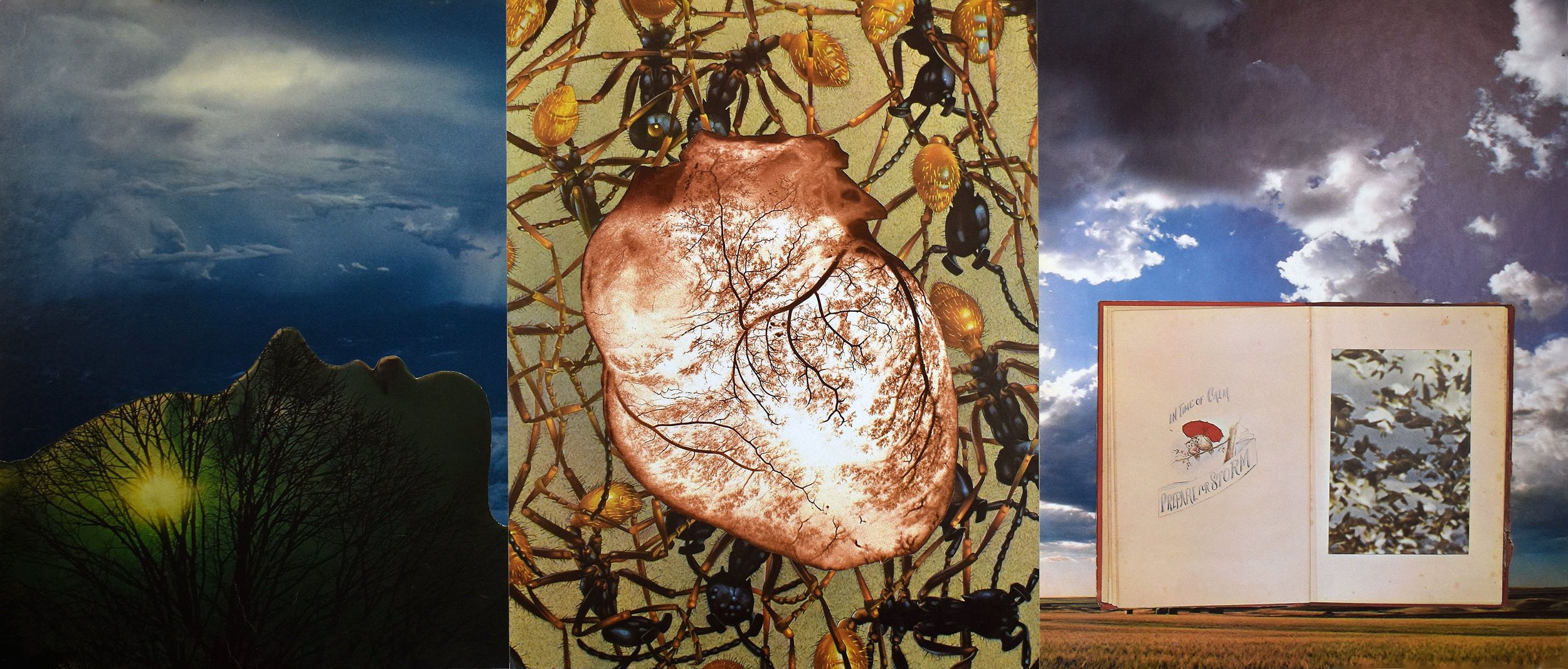

Top: Prepare, 2024, photomontage on board, 12.5 x 29.5 inches.

Bottom: Obsession, 2024, photomontage on board, 11.5 x 26 inches.

Invasive Seizures 2024 Photo montage, found photographs and color pencil, eight panels, each 12.5 x 9.25 inches. Overall length: 100 inches. Right: detail, panel five.