Assemblage

According to the Oxford Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, assemblage in the broadest sense of the term: [H]as its roots in the sculptural experiments of Picasso, in Dada (particularly the work of Schwitters), and in Surrealism (many of whose exponents made objects from diverse materials), but it was not until the 1950s that a vogue for this kind of work began. 1. Loosely applied, the term “assemblage” can cover a broad range of art making, particularly where found material is used: From photomontage to installation art. Collage and assemblage are often regarded as synonymous or meaning essentially the same thing. However, a fundamental distinction needs to be made between collage and assemblage: The former is usually two-dimensional, while the latter is usually three-dimensional. This distinction is not based essentially on the way that material handled, rather, it is based on the way that material is used in relation to how the finished artwork is perceived. While these are terms for closely related techniques, in so far as both involve assembling usually found or appropriated material to make an artwork, it's useful to provisionally distinguish collage and assemblage on the basis of dimensionality, with the proviso that there might be hybrid works that are three-dimensional collages, or conversely two-dimensional assemblages. Just as collage is not restricted to assembling and then pasting paper or cardboard to a flat surface, assemblage per se is not limited to the making of three-dimensional objects. Such hybrid works seem to occupy an intersection between collage and assemblage, or vice-versa. Examples of such hybridity are Compact Record of Discorded Thoughts from 2006, and Mantle (After a fashion) from 2007.

Oxford Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art, “Assemblage,” Oxford University Press, Second Edition 2009, 43

Caged Spring 1976 Assemblage with title label on painted wood base, cage: 9.25x8.25x10.25 inches.

My sculptures are visual metaphors -- Pablo Picasso

In the summer of 1975 I found an odd bit of trash on a street in Oakland, California. Someone had either discarded or lost an 18-inch spring about the diameter of my little finger. It must have been there for some time, hugging the side of the curb almost to the point of invisibility, because it had acquired a full coat of rust. This apparently useless piece of junk did not escape my attention. I did a lot of walking in those days and I always kept my eyes peeled for anything unusual that I might happen upon, anything that stirred my imagination and might be used to make artwork. Earlier in the year I found a small hand-made cage in a thrift shop. It was a humble yet beautiful little object, carefully made of heavy wire mesh, complete with a hinged top and a handle. I bought the cage on impulse, for no other reason than admiration for the skill that went into its construction. The simple and thoughtfully made cage had an unmistakable quality. The long spring also had a certain character, dark, scaly, flexible and potentially sinuous. Yet, it was an artifact that few would give a second thought to, overlooked as just another piece of urban street debris. Collected up that day the spring became more raw material for possible artworks. The cage and the spring were stored separately in my small studio in Oakland for a couple of months. Then one day, looking through my little collection of trash I had a flash of inspiration: The spring was loaded into the cage, its two ends hooked to the inside of the wire mesh. A small typed label was then affixed to its base:

Caged Spring

PJF-76

Art of Bandaging 1977 Assemblage, forked stick and surgical tape with photocopied pamphlet (bandaging diagrams), stick 34x1 inches, pamphlet: 8.5x11 inches.

At some point during their lifetimes some artists experience privation, even poverty. For most the experience is a crucible that either turns their dreams into ashes or forges their spirit, giving them the strength or resolve to follow their creative instincts. Under such circumstances the artist often has no one to turn to for aid: Family and friends may also be struggling or distant, geographically or otherwise. Low paying monotonous jobs or public assistance both come with strings attached and are for many soul crushing. In a desperate attempt to avoid this fate, some artists fall into a dangerous well of substance abuse, depression, or anxiety, any of which can end their lives or at the very least keep them from realizing their full creative potential. These are well-known pitfalls. Perhaps one’s susceptibility to self-destruction is in this case related to either the depth or the shallowness of one's creativity: either the artist is held captive by his or her genius and prey to its excesses, or there is a sinking realization that one is only going through the motions, as it were, playing the role of an “artist”. A true artist is capable of being circumspect, has no need of disguises and knows how to escape the bounds of any captivity, even the sort that arises from within, like drug or alcohol dependency. The young creative artist is an unworked stone who cannot – by virtue of his or her temperament – be shaped by anyone but themselves. But self-realization nevertheless sometimes exacts a cost for the unpolished artist in terms of lost resources and missed opportunities, a cost however preferable to the dehumanization that often results from losing (or selling) one’s soul, another pitfall that can attend commercial success. However, one's art cannot develop entirely in isolation, no one is untouched by the influences of other artists and the culture at large, influences that the artist may not even be aware of. When it comes to the healing and renewal of ourselves others can offer guidance and comfort (and a morally sound society can provide incentives and opportunities for those deserving or in need), but in the end we are on our own. Real, lasting change always comes from within.

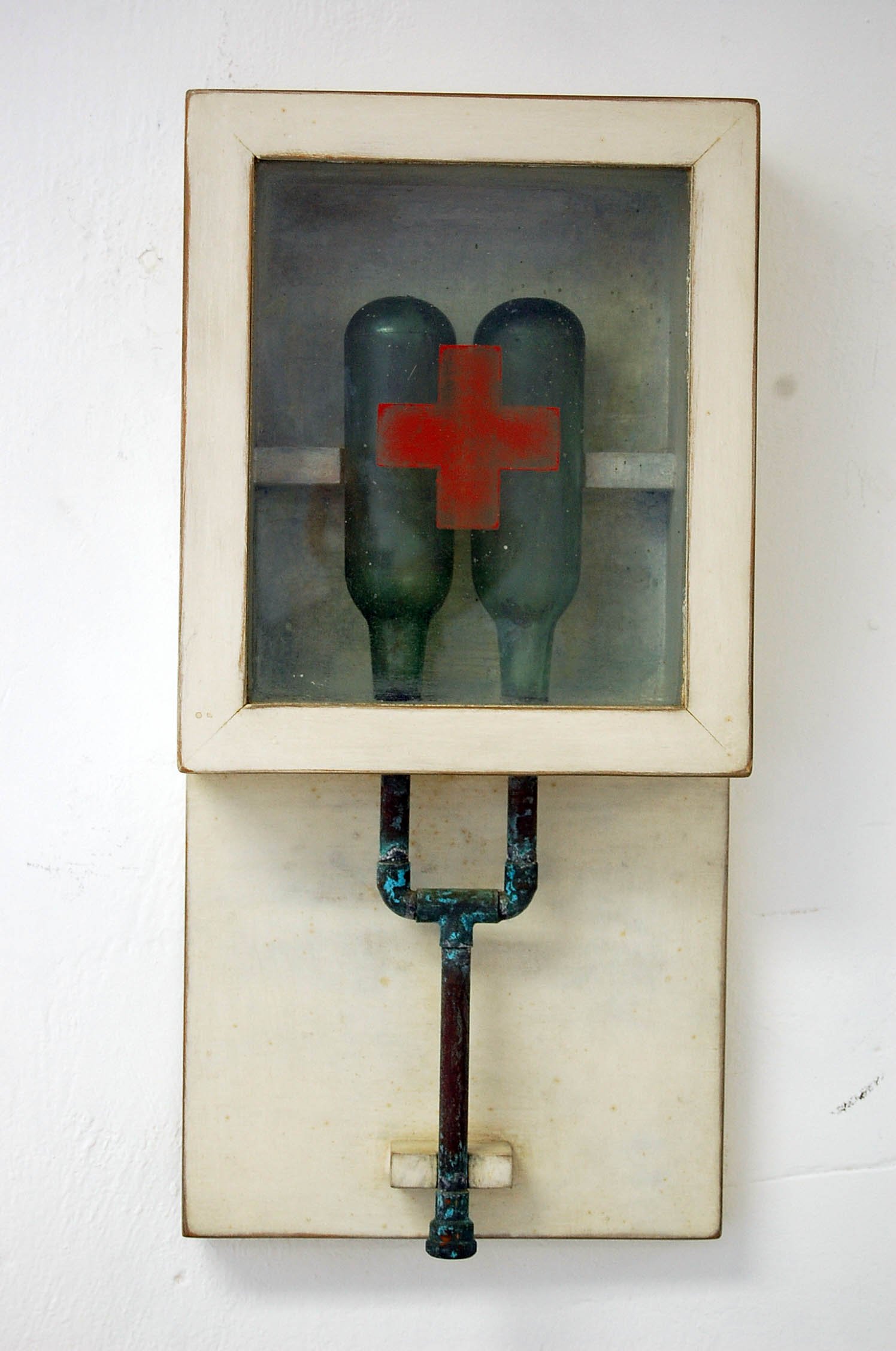

Breathing Station 1991 Assemblage, wood, bottles, plexiglas, copper pipe, 24x12x5inches.

Hooklinesinker 1996 Assemblage, concrete ball, rope, iron hook, ball diameter: 12 inches, hook length: 28 inches, rope 18 feet.

A work of art may be understood as a conductor from the artist’s mind to the viewer’s. But it may never reach the viewer, or it may never leave the artist’s mind. - Sol Lewitt

The Conductor’s Notes 1997 Assemblage, 12 sheet metal stencils of hand shadows in a flat, hinged box with photograph of hand array drawn in graphite on a wall, 16.5x14.5x2 inches.

Landscape of Memory 2006 Assemblage, Removable hand-colored aerial photograph and rust solution on low relief replica set in artist’s paint case. 15x16.5x14 inches. (open).

Probe 2007 Assemblage, oil can, Christmas tree stand, rust solution, 21x11.5x11.5 inches.

Mantle (After a fashion) 2007 Collage/assemblage, dress maker’s mannequin with cut out photocopies, 64x13x10 inches.

Above: Detail.

Artist’s Breath 2008, Assemblage, sealed bottle on brass stand, 13x4.5 inches.

Artist’s Breath is a simple yet elegant little assemblage that at first appears to be an antique lamp but is actually a long-necked oblong bottle attached to a brass and wood base. The work is made from parts of a brass candle sconce that was disassembled and reconfigured, the machined parts fitting together perfectly; the cork in the neck of the bottle also fitting neatly into the recess made for the candle. Given how well everything worked together, the piece seems almost preordained, perhaps less a testament to the ingenuity of the artist than how the chance combination of things sometimes brings marvelous objects to light.

The symbolism of the work stems in part from what the bottle purportedly contains: The trace of a person’s breath. The symbolism of breath is varied and complex. In classical Greece, breath as an archetype was identified with consciousness, locating both thought and feelings in the lungs, which interacted with the heart, blood, and pulse. (The Book Of Symbols, 2012) This suggests that consciousness is obviously and inextricably bound to the body, not merely in the sense that consciousness is (presumably) impossible without a body, but rather that the nature of consciousness is rooted in the body and to a large extent determined by it; that our awareness of being and all the attendant thoughts, feelings and perceptions are ultimately embodied, here specifically in terms of heart, blood, and pulse. Insofar as breath is identified with consciousness, Artist’s Breath "contains" or embodies and thus symbolizes an instance of consciousness, a moment of clarity, or better, inspiration. Given the lamp-like appearance of this work, there is also a suggestion of illumination, a concept that is closely related to inspiration. It’s interesting to note that inspiration is literally defined as "the action of blowing on or into something." (Oxford English Dictionary 2002), thus the act of assembling the work and breathing into the bottle is both literally and figuratively a matter of inspiration. Dawning consciousness, the awakening of awareness, insight, understanding, is always about illuminating the darkness.

This view suggests the dynamism of the psyche, something long symbolized by light and by extension all instruments that cast light, such as a lamp. The archetypal perspective is again instructive: Circumscribing its illumination of darkness, the Lamp has been associated with consciousness and its capacity to sustain the flame of life, hope, freedom, creativity and the sacred and the divine. (Book of Symbols, 2012) Breath also animates, as in the proverbial “breath of life.” Together with illumination, animation in the fundamental sense of bringing something to life, also implies creativity. If the symbolic meaning of breath is combined with the notion of illumination, then Artist's Breath is a relic or memento that celebrates an inspired or creative life.

The Book Of Symbols, Editor Ami Ronnberg, Taschen, 2012, "Breath," p. 16. Ibid. "Lamp/Candle," p. 580. Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 1396.

Small World 2008 Assemblage, magnetized steel globe with metal objects on Oak base, 20x12.5x12.5 inches.

As many of us know, greenhouse gases act as a "blanket" to basically trap the radiant energy of the sun, absorbing and also emitting this energy back into the environment. But our planet, the only home that we have, is not only enveloped by more and more water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane, we are told by NASA and other agencies that it is also shrouded in a massive and ever growing cloud of space debris. According to the U.S. Strategic Command, as of 2016 there were a total of 17,852 artificial objects orbiting above the planet. That is a lot of space junk, and that's just the stuff large enough to track. It seems that there are literally thousands of tons of debris in low earth orbit (LEO), a fact symbolically represented by Small World. This assemblage is made from a little steel globe imprinted with oceans and continents atop a wood base festooned with a variety of metal objects: rusty nails, wires, nuts and bolts, springs, and so forth. The objects are held in place by hundreds of little round magnets lining the inside of the globe, an elegant solution to the problem of how to attach the objects to the metal sphere that also suggests another fact: that the earth has a magnetic core.

It should be noted that it is possible to see space junk as the direct result of runaway space technology and seemingly unrelated to climate change. Whether space debris - particularly stuff ten centimeters and under - is somehow a contributing factor in the earth's warming is unknown (much like green house gases such particles may contribute to containing the planet's heat). The fact is, much like the accelerating accumulation of greenhouse gases in the earth's atmosphere, space junk has also shrouded the planet. It might be argued that this orbiting mantle of junk is yet another form of pollution, and even though it is largely invisible to us on the ground its substantial nature makes it emblematic of our poor stewardship of the earth. Small World metaphorically represents this disturbing situation, a development that in turn suggests the continuing degradation of the planet through our seeming indifference or lack of resolve.

Ringing Silence 2012 Assemblage, alarm bell, map, biology textbook pages in a wood case, 13.5x16.75x12.5 inches.

Much like Small World, Ringing Silence carries a political message concerning the precarious state of the natural environment. The work is a wood case housing a red alarm bell, a map of the arctic (with lines of latitude emphasized in red), and biology textbook pages on the theory of evolution. An alarming (pun intended) global temperature graph on the front page of the February 7th, 2019 issue of The New York Times plots the steady overall climb in the earth's warming since 1880. The graph forcefully drives home the fact of global warming, which is now accelerating climate change, something that is becoming more and more evident through increasingly erratic weather, sea rise, and other weather related disasters. If the majority of the planet's people are aware of climate change (perhaps many are even aware of our role in all this), then how useful is art in this context? Is science, rather than art, better equipped to further educate the public about the dire predicament that we humans are contributing to? Such questions, it seems, in turn raise questions about the efficacy of politically motivated art.

Does art like Ringing Silence, art with a social or political message, unequivocal or otherwise, serve any real purpose, for instance, in terms of activism? Can art contribute anything substantial to what is already understood by many in relation to our existential predicament? Can or should art take on a moral responsibility through, if nothing else, the issuing of warnings, proclamations, and so forth? Ringing Silence issues a clear and unequivocal warning about climate change, suggesting by virtue of its title the dark possibility of that old adage: "out of sight, out of mind." While few of us will ever find ourselves in the arctic witnessing disappearing ice, many of us are now experiencing the disastrous effects of a warming planet in terms of heat waves, raging forest fires, intense storms, flooding, and more. The question is: Given our growing awareness of the seriousness of the situation do artworks like Ringing Silence serve any real purpose? Or does this work and work like it reduce an existential crisis to a few safely contained symbols and merely act to defuse or downplay an explosive reality, and if nothing else morally and emotionally placate the artist and his or her audience? It may be that art with a message is ultimately ineffective, that direct action is the only thing that offers the possibility of turning the tide. I believe that this is true, yet there is no reason to abandon making art with a message, particularly if doing so strengthens the artist’s and the audience's commitment to speak out and get involved. One thing is certain, by effectively presenting a fact by way of an idea in concrete form an artwork can carry a greater emotional charge than a mere proposition stating the same fact.

Twilight of Eden 2015 Assemblage, Found box with small fragments of concrete with photo transferred traces of a reproduced 19th century landscape painting, framed engraving on lid, 13.5x11.75x17.5 inches.

Giordano’s Window 2019 Assemblage Silver leaf & ink over book covers in artist’s frame, 39.5x 31x1.5 inches.

Old books have long played an important role as sources of raw material for my collages, assemblage pieces, and the occasional “book work.” Book works – an art form that physically modifies books while retaining some aspect of their identities as such – have been made in countless ways by artists working in this genre. One way involves using whole books or their parts in physical constructions, thereby transforming vessels that contain words and pictures into something potentially meaningful. Giordano’s Window is a prime example; an intuitively conceived book work/assemblage hybrid using the ornate covers of a set of old reference books.

To fully appreciate the meaning of this work, a brief backstory is helpful. In 1591 a Venetian bookseller named Giovanni Battista Ciotto extended an invitation to philosopher and magus, Giordano Bruno to visit Venice at the behest of Zuan Mocenigo, an important member of the Venetian nobility. Bruno, living in Frankfort, Germany at the time was a respected authority on the art of memory and other esoteric subjects, and thorn in the side of the Catholic Church. Mocenigo wished to learn of the secret art of memory from a master practitioner. For his part, Bruno saw an opportunity to secure lecture dates to expound upon his views of a much-needed reformation of the Catholic religion and possibly garner the blessing of none other than the Pope for this mission! Bruno, a defrocked Dominican, accepted Ciotto’s invitation and in 1592 moved into the Mocenigo household to begin instructing the wealthy scion. Bruno was passionate about his mission as a religious reformer and at times could be volatile, even fiery, which doubtless would be his undoing. It is possible that Bruno eventually grew distrustful of the devout Mocenigo’s motives for inviting him and planned to return to Frankfort at the earliest possible date. Mocenigo was by then in touch with the Venetian authorities, which he alerted after falling out with Bruno and locking him in a room in his house. This sadly was the beginning of Giordano Bruno’s long incarceration, ending with his death at the stake in Rome at the hands of the Inquisition in February of 1600. Particularly germane to Giordano’s Window is the fact that upon his arrest by the Venetian Inquisition Bruno was in possession of a number of “conjuring books,” works on magic that were certainly considered by the authorities as treatises on the dark arts. One can imagine Bruno trapped in a room in Mocenigo’s house with locked shuttered windows, surrounded by and tragically condemned by the books that were the mainstay of his faith.

Detail: Giordano’s Window

Paradise 2021 Assemblage, photocopies, wallpaper, wood, mixed media on board, 43x48x 1.75 inches.

Paradise, is a large, wall mounted assemblage that refers to an actual place, a small town in northern California. The assemblage creates the illusion of a window framing what at first appears to be trees etched against a sunset. A closer look, however, reveals something disturbing: the red and orange sky of a fire, flecked with embers, a burn threatening to incinerate the window. An idyllic image is transformed. In a heartbeat Paradise becomes Hell. This initial misperception is instructive: what we think we see sometimes obscures the reality of our lives. As such, Paradise symbolizes an interrupted state of mind, of contentment and happiness. For the residents of Paradise, that interruption began on November 8, 2018, when the worst fire in the state’s history, the ominously named “Camp Fire,” devoured almost the entire town of Paradise in a hellish nightmare that took 85 lives. The fire that destroyed the Sierra Nevada foothills town was a wakeup call not only for Californians facing increasingly higher average temperatures and devastating droughts, but for anyone concerned with the effects of climate change. The community of Paradise has vowed to rebuild, and hundreds of new homes have been constructed since the conflagration. But many remain wary and every plume of smoke in the hills surrounding the town is cause for alarm. Simply rebuilding safer structures might mitigate personal risk but given the accelerating effects of climate change the surrounding environment remains vulnerable to more “one-hundred-year fire events.” Paradise, originally a community of largely lower income people, many retirees, is a metaphor for the longing of people to find solace in a natural setting. Living in Paradise was also the realization of the dreams of many of these people; collectively the dream of enjoying the bounty of nature, the fragrance of Redwoods, the sparkle of mountain brooks, and the calls of Spotted Owls. Their loss, and the loss of this bounty is a tragedy. This, indeed, seems to be our fate, this and our intractable belief in our power to overcome adversity.

Miami 2022 Assemblage, wood, plexiglas, paper, mixed media on board, 44.75x48x1.75 inches.

For some, the sun-drenched city of Miami, Florida projects an aura of glamour; a metropolis that still embraces the “American Dream.” At one time, Miami was one of the destinations of snowbirds and retirees. Miami seemed to be the perfect place to spend one’s golden years, if one could afford to live there. In spite of the fact that there are no state income taxes, the city of Miami has one of the highest cost of living indexes in the nation. Like many big cities Miami is also plagued by crime and poverty, and according to recent statistics, with violent crime even higher than New York City. Miami is divided along class and race lines with many of the poorest sequestered in urban ghettos like Overtown and Liberty City, while the well to do (and mostly white) populace enjoy lifestyles a world away in gated communities in South Beach and Coral Gables.

Miami is meant to suggest a connection between economic poverty and the sorts of internal impoverishment that contributes to if not drives despair and a host of social ills. Sometimes such malaise leads the disadvantaged among us to withdraw from the world, symbolized by the papered over window of Miami. Economic deprivation alone doesn’t necessarily produce social isolation, although it’s often an underlying condition. There might be other factors at play, including the mental and/or physical well-being, age, or anti-social nature of the person or persons hiding from the world. In this regard, Miami seems to communicate something by way of the newspaper and magazine clippings covering the window. The various headlines, add copy, and so forth, allude to the aforementioned despair, but also to alienation and paranoia, among other things. Miami graphically implies that the personal problems that are so often hidden away are related to or at least exacerbated by the physical, socio-political and economic environment that individuals find themselves in, usually the poorest and most disadvantaged. Most poor people in Miami and elsewhere do not pull back from the world, many struggle every day to make ends meet and contribute to society in spite of their hardships. The point of this assemblage is: Many of the poor often struggle in ways that go unseen; confronting the daily grind while feeling left out, forgotten, coping with shame and helplessness.

Asylum 2024 Assemblage, Mixed media on board, 40x48x1.75 inches. Above: detail